PAINT AS YOU LIKE

A son takes an emotional journey through his father's life as an artist and explores universal themes. What is success? What is failure? What is art?

Trailer

About

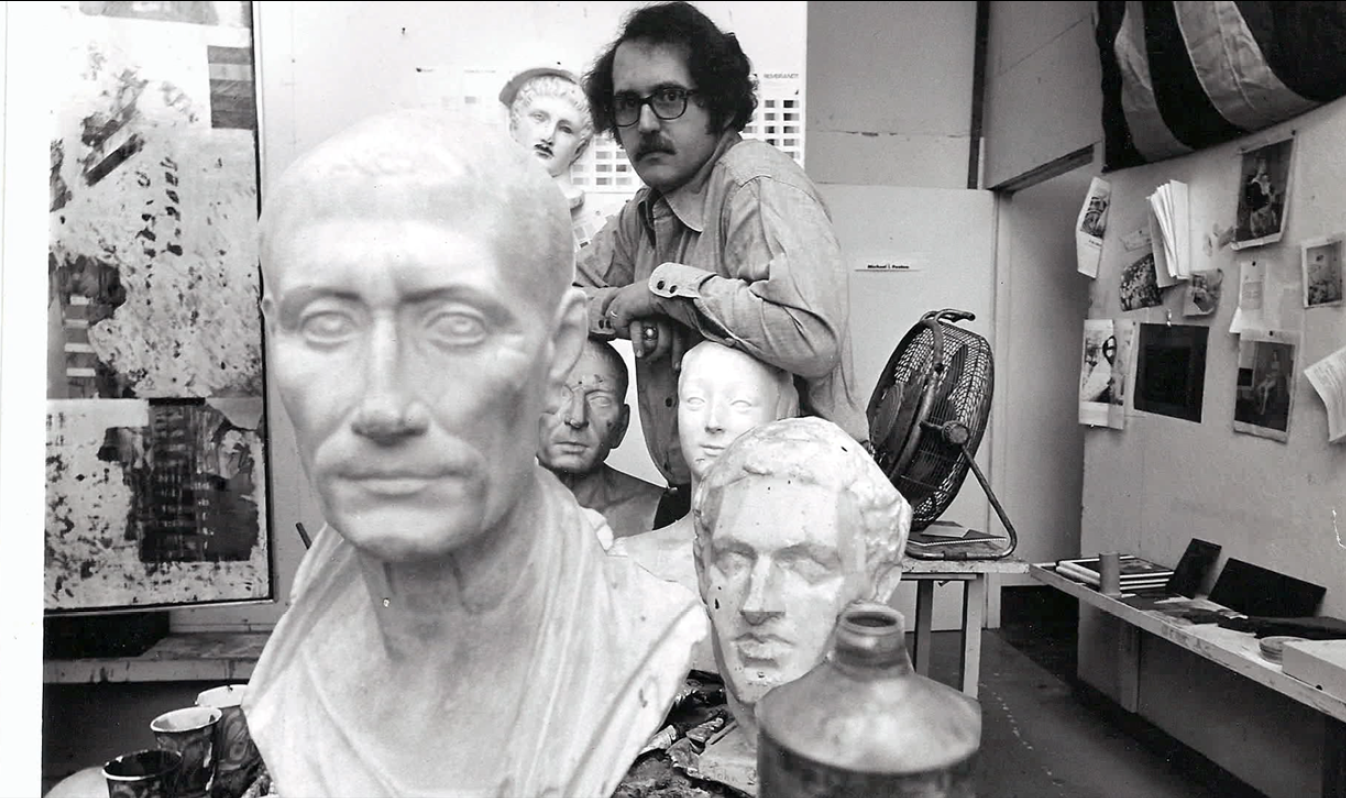

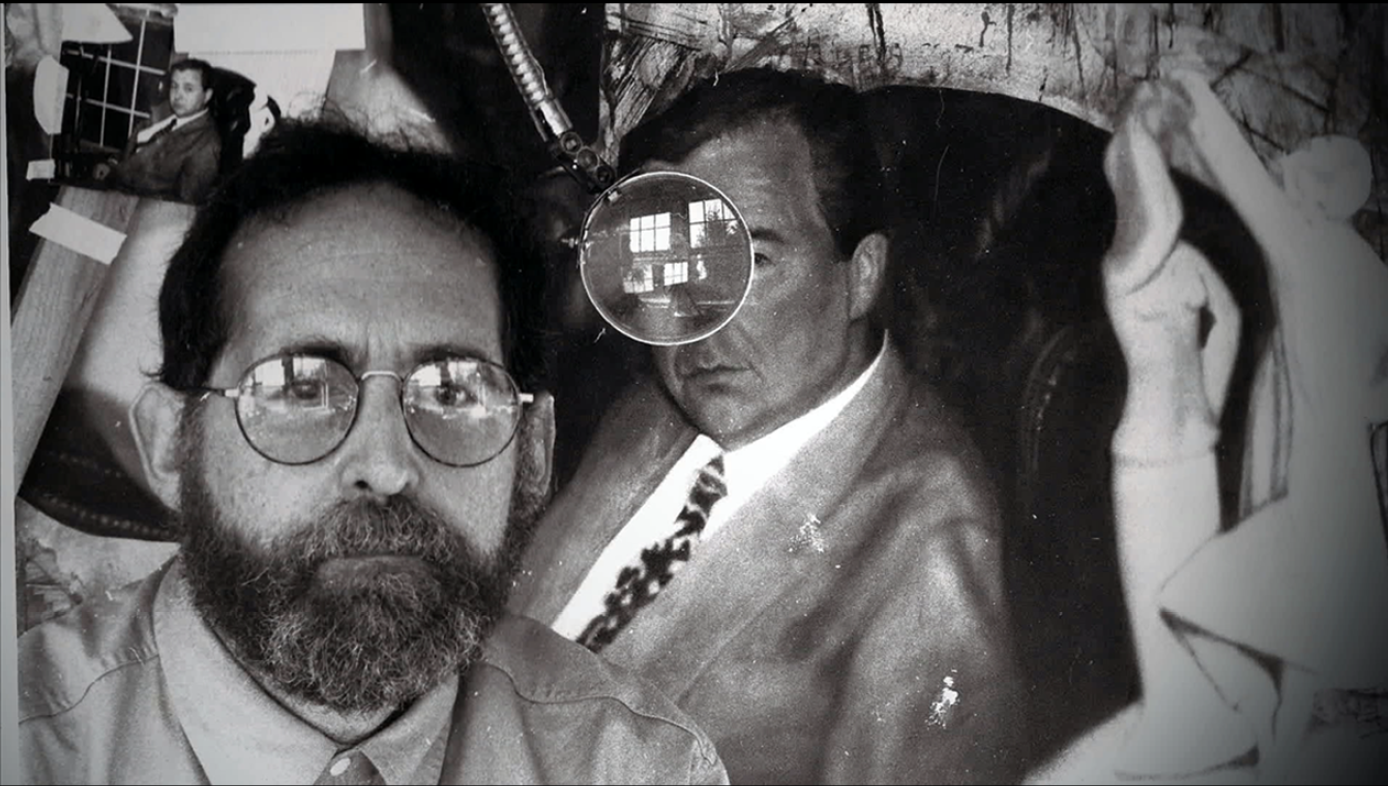

Fresh out of art school, Michael I. Fenton sold his first painting to the Cleveland Museum of Art. At the age of 25, he was well on his way to making his mark in art history. Michael's son, filmmaker Ryan Fenton-Strauss, takes us on a journey through 50 years of his father's work, from abstract expressionism to narrative painting. Paint as You Like weaves together biography and art to tell an often comical and sometimes painful story of an artist's life. Father and son, uniquely connected by their passion for art, explore universal themes. What is success? What is failure? What is art?

RUNNING TIME 64 MINUTES

Screening

Utopia Film Festival

Saturday Oct. 14th 2017 at 12PM

Santa Fe Film Festival

Saturday Feb. 10th 2018 at 10AM CCA Center for Contemporary Arts

Idyllwild International Film Festival

Thursday Mar. 8th at 1:55 PM other showing Saturday Mar. 10th evening

Filmmaker

Ryan Fenton-Strauss has been working for the past 13 years at The USC Shoah Foundation, a non-profit organization founded by Steven Spielberg to preserve the memory of the Holocaust. Ryan oversees the preservation of video testimonies given by genocide survivors. He also runs a video production group to promote the educational mission of the USC Shoah Foundation. He directs and edits numerous short documentary films, and educational and promotional videos. Several videos have been featured on Comcast Xfinity On Demand.

In addition, Ryan has produced and edited a number of political videos, which have played at the Democratic National Convention, and another that was recognized on Chris Mathews' Hardball. He has written two feature scripts, one of which was a Fade In Screenwriting Award Semifinalist.

Ryan Fenton-Strauss earned a BA in Theater at Brandeis University and an MFA in Film Production at Chapman University. Post graduation, Ryan returned to Chapman to do adjunct teaching at the Dodge College of Film and Media Arts.

Q & A with Ryan Fenton-Strauss

Why did you make this film?

Why did I do this thing? Well, I think it goes back to when I was asked to be a videographer for an interview with Michael Hagopian, as part of my work at the USC Shoah Foundation. Michael was a 97 year old survivor of the Armenian Genocide, and he had spent his life making films about it. During the breaks, we would have conversations. He told me was planning his next documentary, which he was going to shoot in India. And I had the thought, if this guy at 97 years old with no film crew was running around the globe making films, then what was my excuse? I told him I was thinking about making a film about my father. He told me that his greatest regret in life was not putting his father on camera while his father was still alive. And that cemented in my mind that I needed to do this.

What originally gave you the idea to make a film about your father?

I think this story has always been with me, and in many ways it's plagued me my whole life. The need to make this film comes from my own psychology. I feel like I've been burdened by an unhealthy outlook on my work: when I get involved in my projects, there's this feeling, this manic energy - I need to make it. My whole ego gets wrapped up in the process of making it, and by the time it's done, I hate it and I think it's terrible, and I'm nobody and nothing, and what have I done lately? So I think a big part of making this film was about trying to get to the root of my own anxiety.

Why does your film open in a graveyard?

I think everyone has to deal with this: their parents are going to die. But for me there's this added thing that there's this attic full of paintings. My father managed to keep painting for 50 years, and a lot of it is really good. I think there's something sad and painful that this stuff is just sitting there. I think that in the back of my mind, I was thinking, wouldn't it be a great end to the story if this film somehow gets noticed, and that helps preserve his legacy? In a way, that would be the ultimate outcome.

What was the hardest part about making this?

It's hard to think of something that wasn't hard about it. That's the Fenton thing. That struggle is always an important part of the work. And so when you look back, you say, what went smoothly?

What are you most proud of about it?

I don't do proud.

Ok, so, if you did do proud?

I think just climbing the mountain, you know?

So can you say something about your relationship with your father and how that played into your wanting to make a movie about him?

As a kid, I really did spend a lot of time learning about his paintings. And when he has ideas, now, even today, he sends them to me. He knows that I'm going to reject the first six that he sends me. And he was always very critical of me, too, but that gave me an openness towards criticism and it pushed me to do something better. Obviously, I was very close with him growing up and the bond stayed very strong throughout my adulthood.

What do you think of your father's paintings?

I think growing up, I couldn't explain all the abstract work to my friends. I used to think, for years he did all this abstract work, and then he eventually actually learned to paint. But then, spending time with it while I was making the film, I could see what was going on, I could appreciate it more deeply. But I actually think with his more recent narrative work, his painting skills have been getting better and better. For me, there are times where the ideas and the skills come together really nicely. That's what I like the best, when the whole thing seems to connect. Now I think his skills are actually quite remarkable.

What is the relationship between painting and filmmaking in your documentary?

When you stare at a painting, your eyes dart around and you can walk up to it, and pull away. I would say that part of my goal was to give the viewer the experience of being able to engage with the painting even though they can't, physically. The other thing I tried to do was to allow the feel of the paintings and the feel of the older photographs to create a visual style. I had this treasure trove of super 8 film from my grandfather. If I didn't have that, I wouldn't have a film. Most people have some of that, but do they have it of their grandparents and their father as a child? I got really lucky. So I was able to allow the feel of that super 8 film, which has that beautiful scratchy look, to influence the visual style of the film. So for me, it's about where the medium and the message collide.

So what is success?

Completing it. I'm still uncomfortable with the idea of success. There's a need for praise, but I only want enough to know that I didn't completely screw it up. I don't want to spend my time saying, 'wow, I'm great'. There are moments when I can say, 'okay, this part came together'. But as I look back over my work, I want to be able to say that I'm getting better. For me, success is pouring all of your energy into something, completing it, and then being able to do look at it and say, 'this is what I like about it and this is where I want to go next.' I think that's it.

Photos